INTRO

Refernce: Microsoft Docs C Language Documentation

C programming language is a predecessor of the B programming language for UNIX software development. Currently, C language is the most widely used programming language and had influenced C++, C#, Python, Java, and more. The C language has a faster processing speed and excellent compatibility, making it still great use for application and firmware development.

Compiled Language

There are two different categories of program languages based on its execution: compiled language and interpreted language.

An interpreter allows a computer to reads the source code written in English and execute directly, mostly benefitting from cross-platform support that can run the program on a different system and architecture. Python is one of the best examples of an interpreted language. However, a compiler generates an object file written in machine-friendly code by translating from English-written source code.

C language is a compiled language that doesn’t support cross-platform, but it processes faster than interpreted language due to its optimization to the current system.

Compiler

C language categorizes its compiler version by the year of standard released by the International Organization for Standardization(ISO); ANSI C (aka. C89) and C99 is the most commonly used version. This document introduces C language based on the ANSI C compiler.

Preprocessor

A preprocessor is responsible for optimizing the source code before the compiler translates to binary code. A command for a preprocessor is called preprocessor directive and has octothorpe # at its prefix.

| DIRECTIVES | EXAMPLE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

#include |

#include <iostream> |

Includes header file to the script. |

#define |

#define SQUARE |

Defines new macro for the project. |

#pragma |

#pragma once |

Provides additional options for the compiler. |

A preprocessor does not read C language source code nor follows C language syntax. It only processes its directives, removes comments, and provides optimized source code to the compiler. A preprocessor directive isn’t necessary but makes the coding easier and convenient. The preprocessor resides within the compiler program.

INSTALL

A compiler for C is essential when developing with C programming language, and there are various C compilers available designed by different companies and organizations. The compilation method may differ depending on the compiler, but it doesn’t matter for general users as every compiler observes the same ISO standard that defines the working mechanism.

An integrated development environment (IDE) is a software development program that provides a source code editor and program build tools, compiling source codes to an executable program. This chapter introduces the installation and configuration of an IDE for a C language project.

Visual Studio

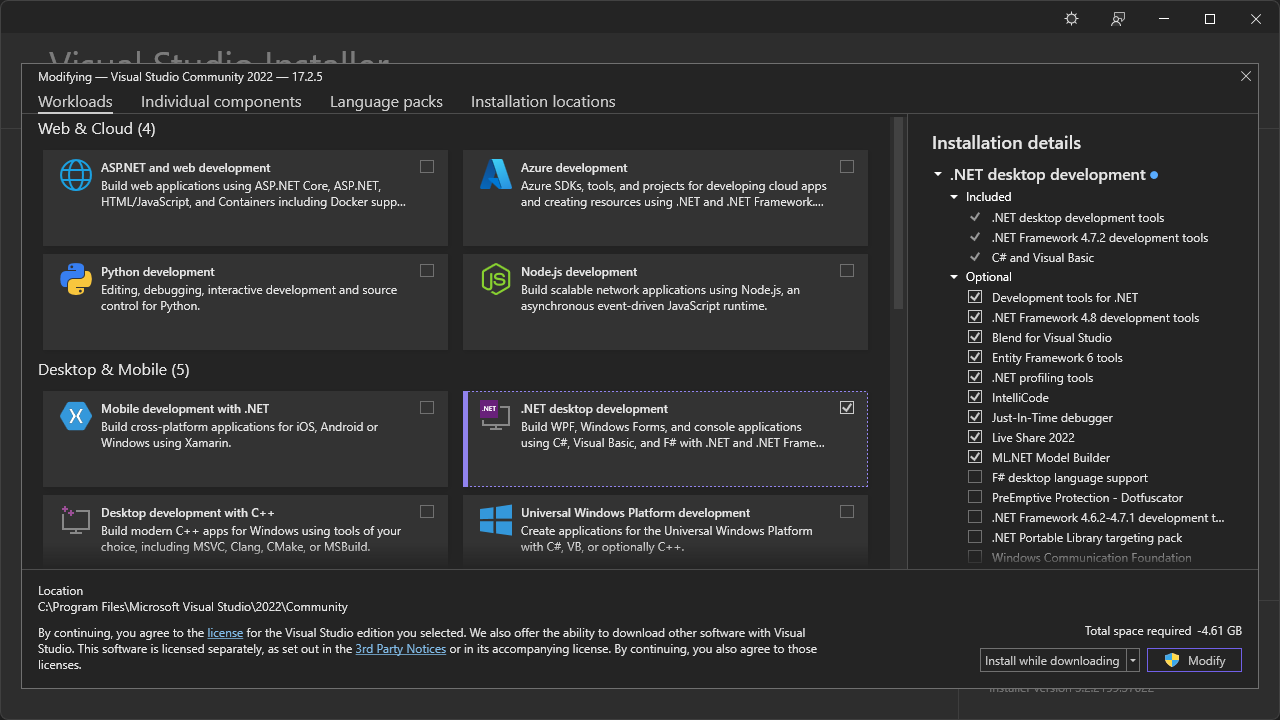

Visual Studio is the most renowned IDE for Windows OS developed by Microsoft, which uses the MSVC compiler. There are three editions for Visual Studio, and the free community edition is enough for development. The IDE provides various components to support different languages as well; for C programming, select the “Desktop development with C++” workload.

The reason to select the C++ workload is that the MSVC compiler is mainly a C++ compiler that also compiles C language. Visual Studio does not have a workload for pure C language development.

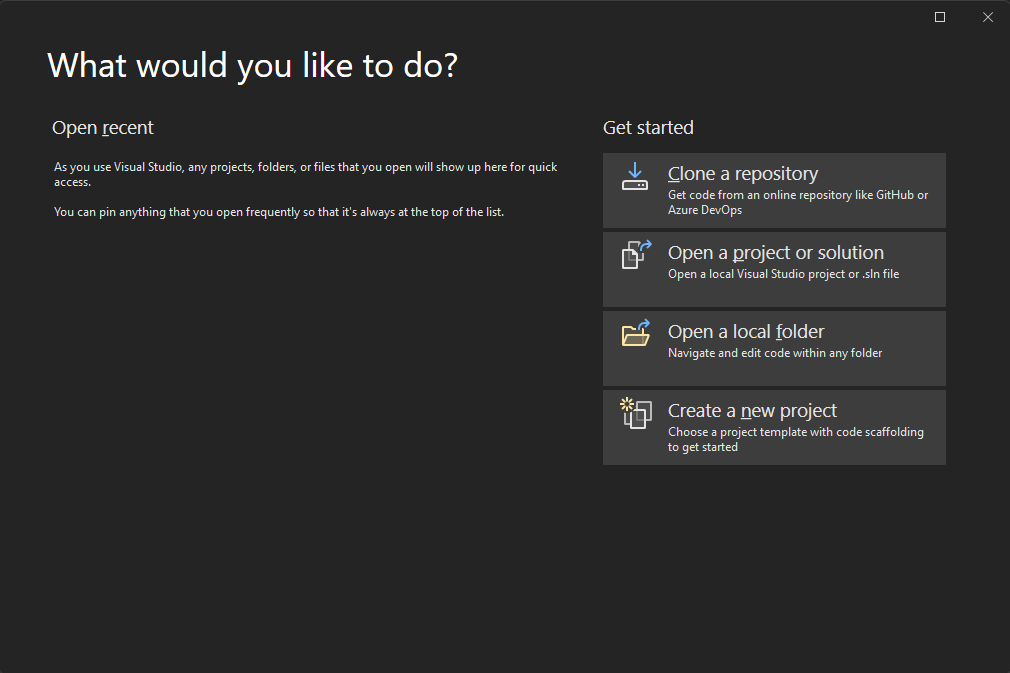

Visual Studio will start with the window shown below. To create a new project for C language, select the “Create a new project” button.

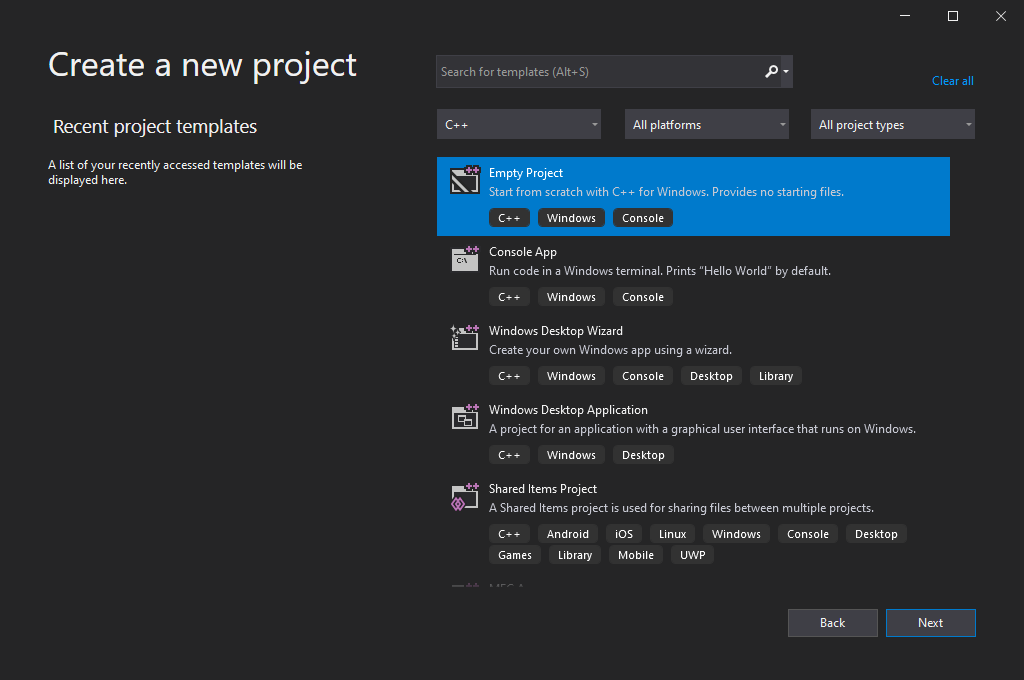

However, Visual Studio does not have an option to create a project for C language since it is all integrated into C++ components. To create a C project, follow the procedure below:

- Select the language as C++ and choose the “Empty Project” option.

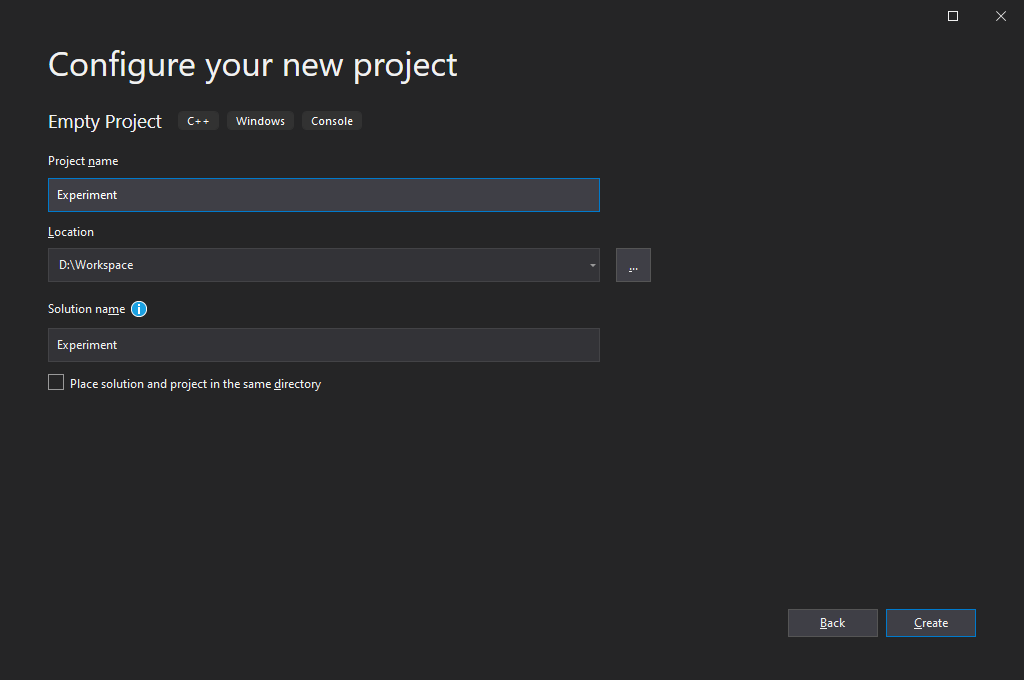

- Designate names for the project and solution. Here, the project is a

.vcxprojextension file that manages its source codes and compilation options, and the solution is a.slnextension file that can contain multiple projects. It is recommended to open the solution file on Visual Studio unless you only want to open a single project.

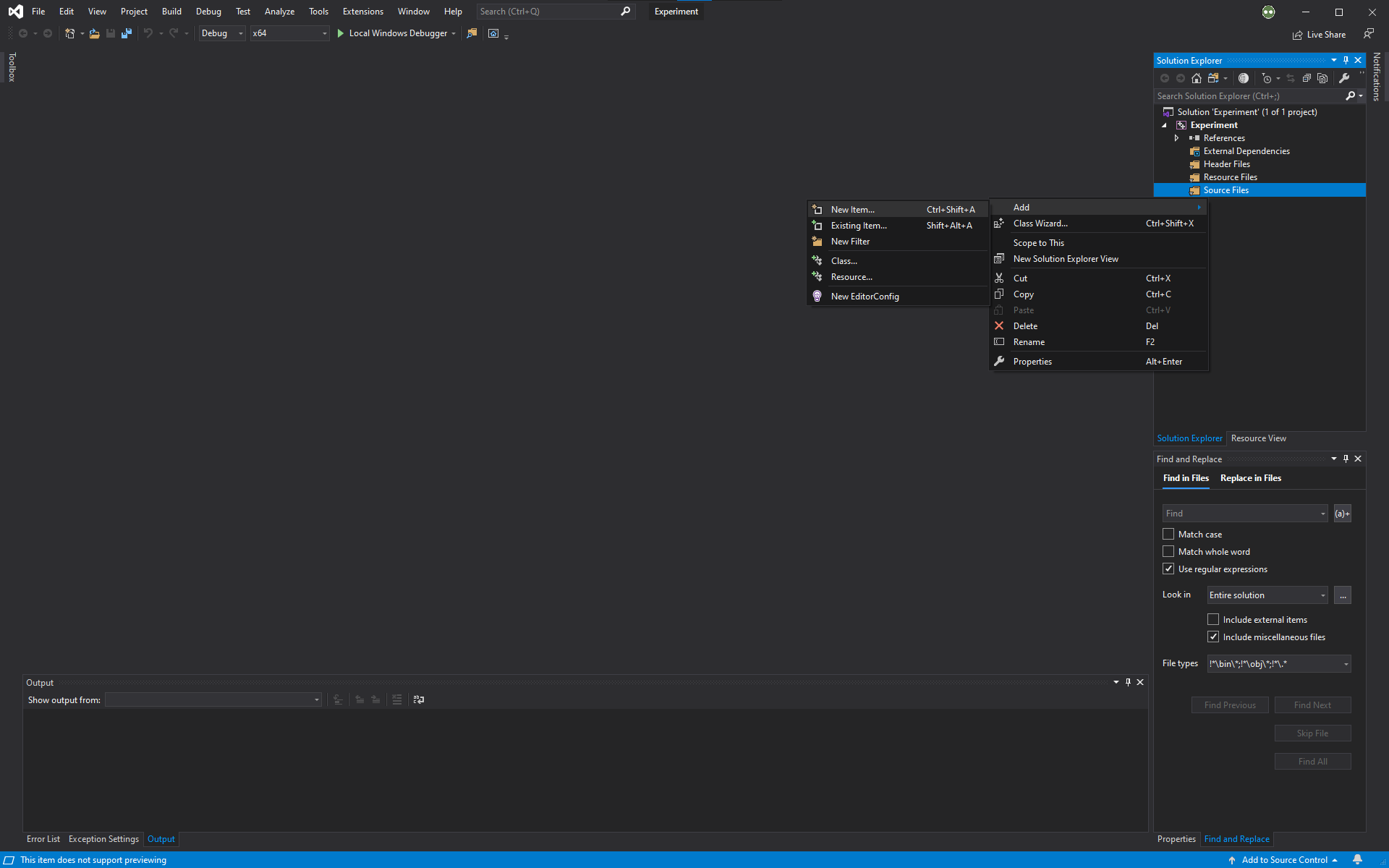

- On the Solution Explorer, right-click the Source Files filter and select the

Add > New Items...option.

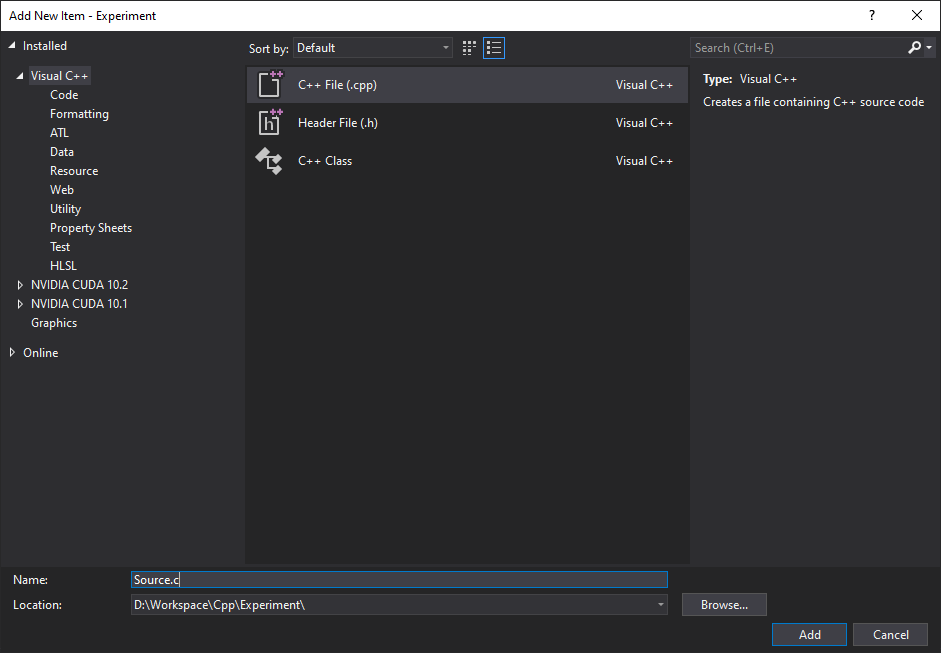

- On the Add New Item window, change the extension from

.cppto.c, which is a source code extension for C language.

Since this is an empty project, there won’t be any code written on the source code. Paste the code below to make the source code at least compilable for the C project.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Insert code here...

printf("Hello, World!\n");

return 0;

}

Visual Studio can run a C language program in two different ways: debugging mode (F5) and without debugging mode (Ctrl+F5). Debugging mode is used to inspect the problem and visualize the process, otherwise run without debugging is recommended.

CRT Security Warning

C Run-time Library (CRT) is a C++ standard library that also contains the ISO C99 standard library. For stability reason, the MSVC compiler has restricted some functions and replaced them with more stable ones suffixed by _s. Attempting to use restricted functions results in compilation error C4996 related to stability warning.

CRT warning commonly appears when programming with C language. However, this is just a warning that can be ignored by the preprocessor directive below:

#define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS

Xcode

Xcode is the most renowned IDE for macOS developed by Apple, which uses the clang compiler. Xcode supports various languages, and unlike Visual Studio, Xcode has a project option for C language.

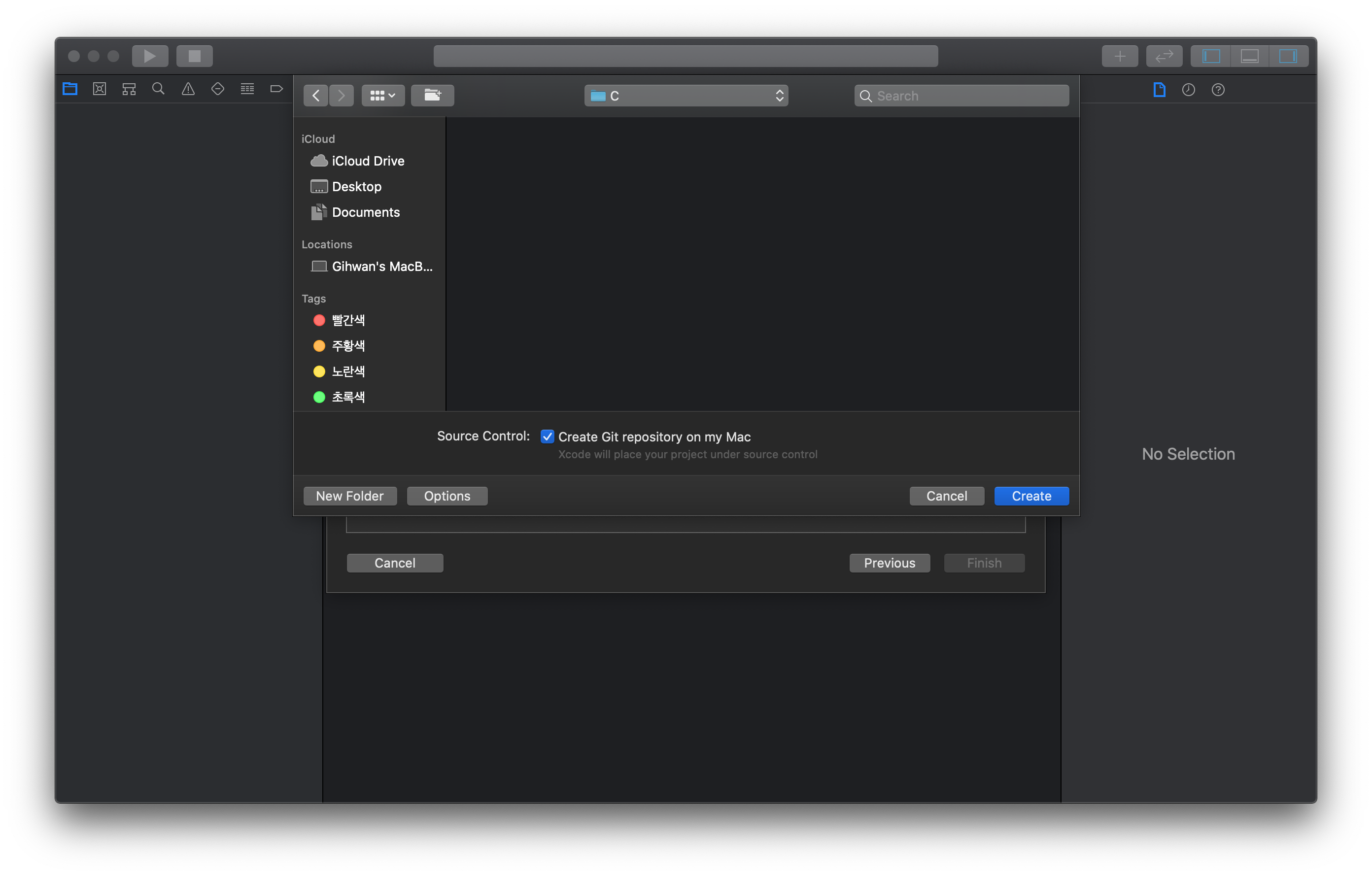

Start Xcode, then create a new project by selecting File > New > Project....

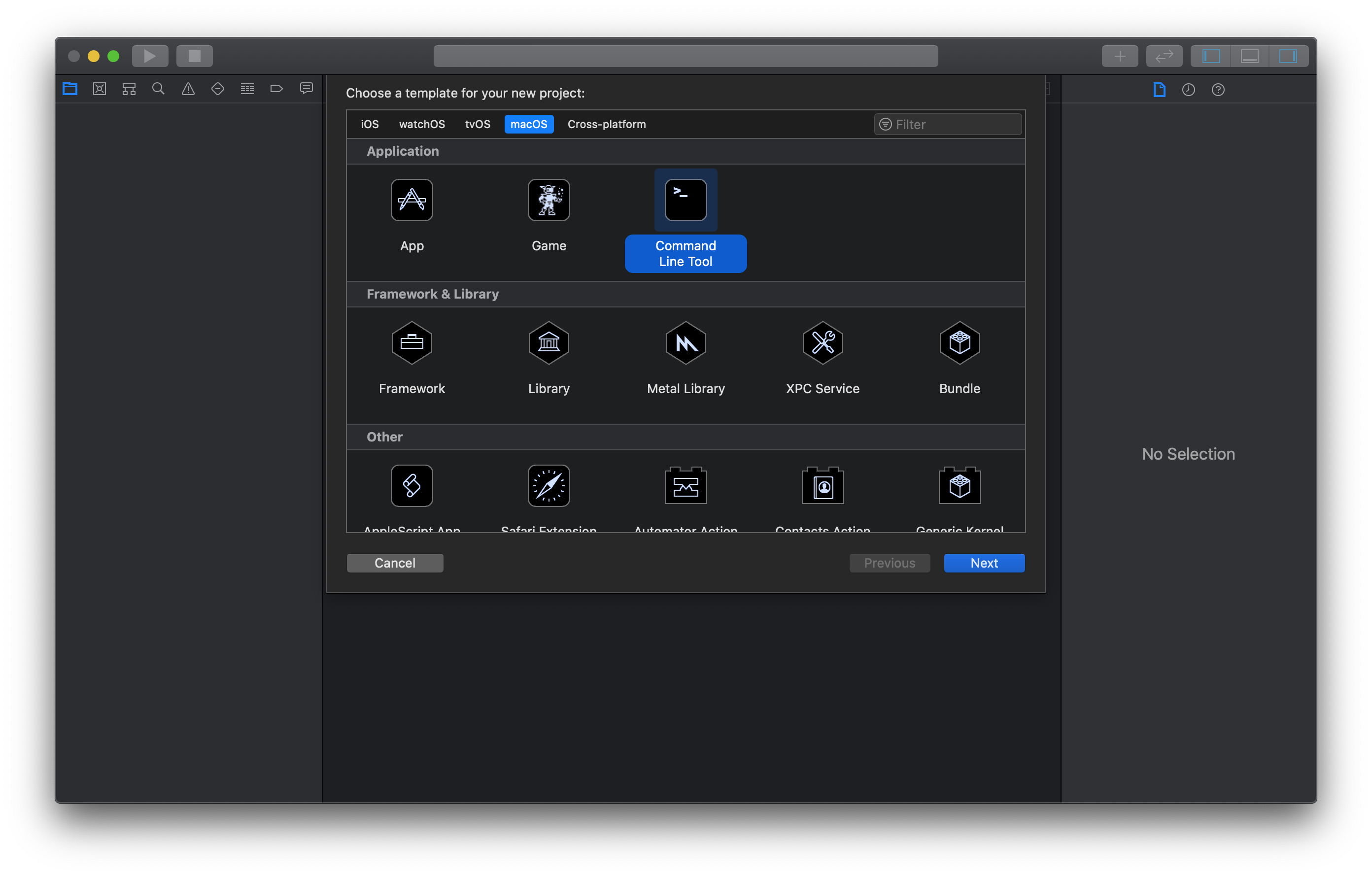

There are various projects available for developing an application for Apple’s product. To create a C project, follow the procedure below:

- Since the computer is macOS, select the macOS tab, then the Command Line Tool to execute a terminal-based program.

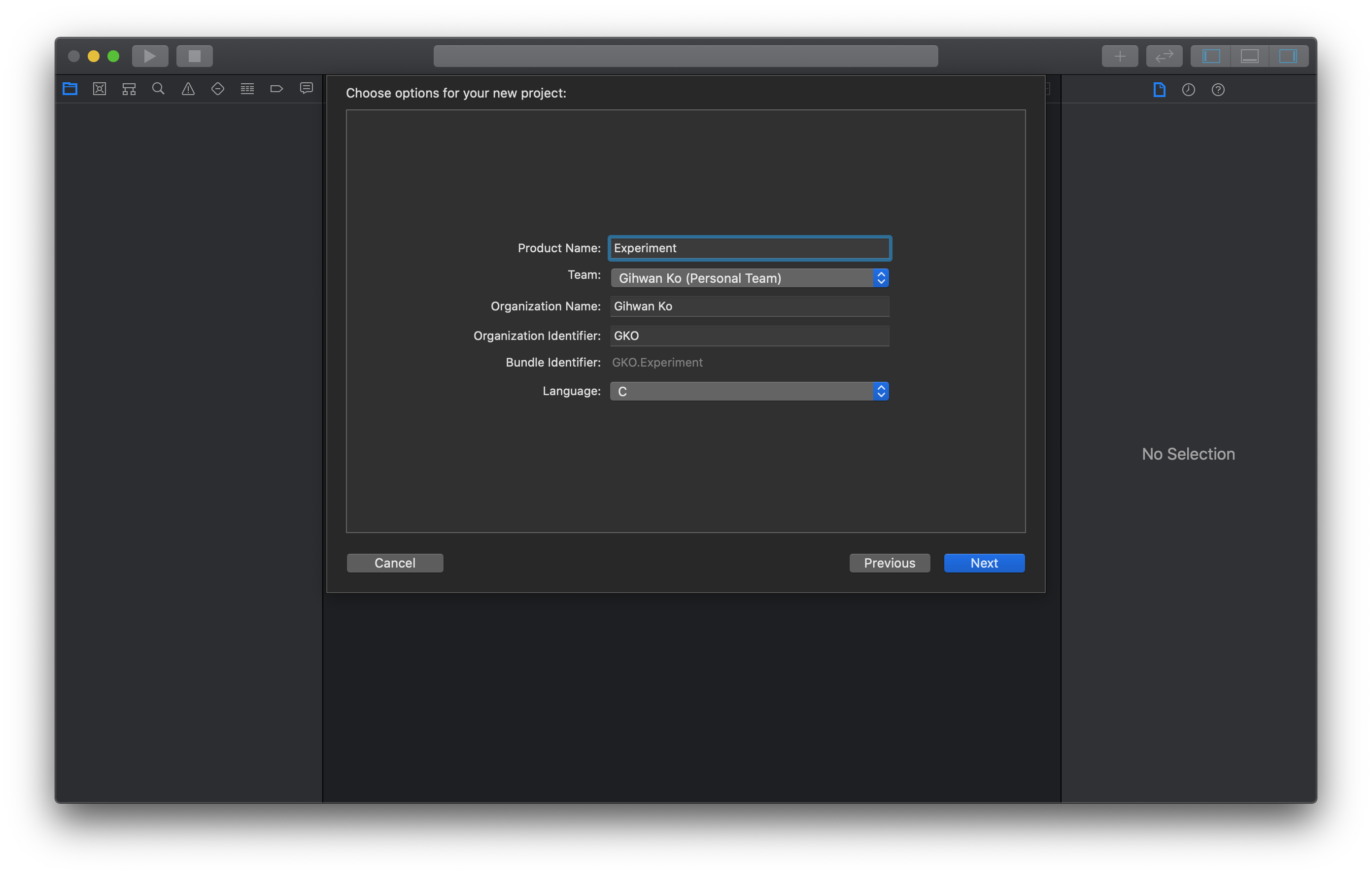

- Name a project in the Product Name and select the Language as C.

- Designate a path for the project.

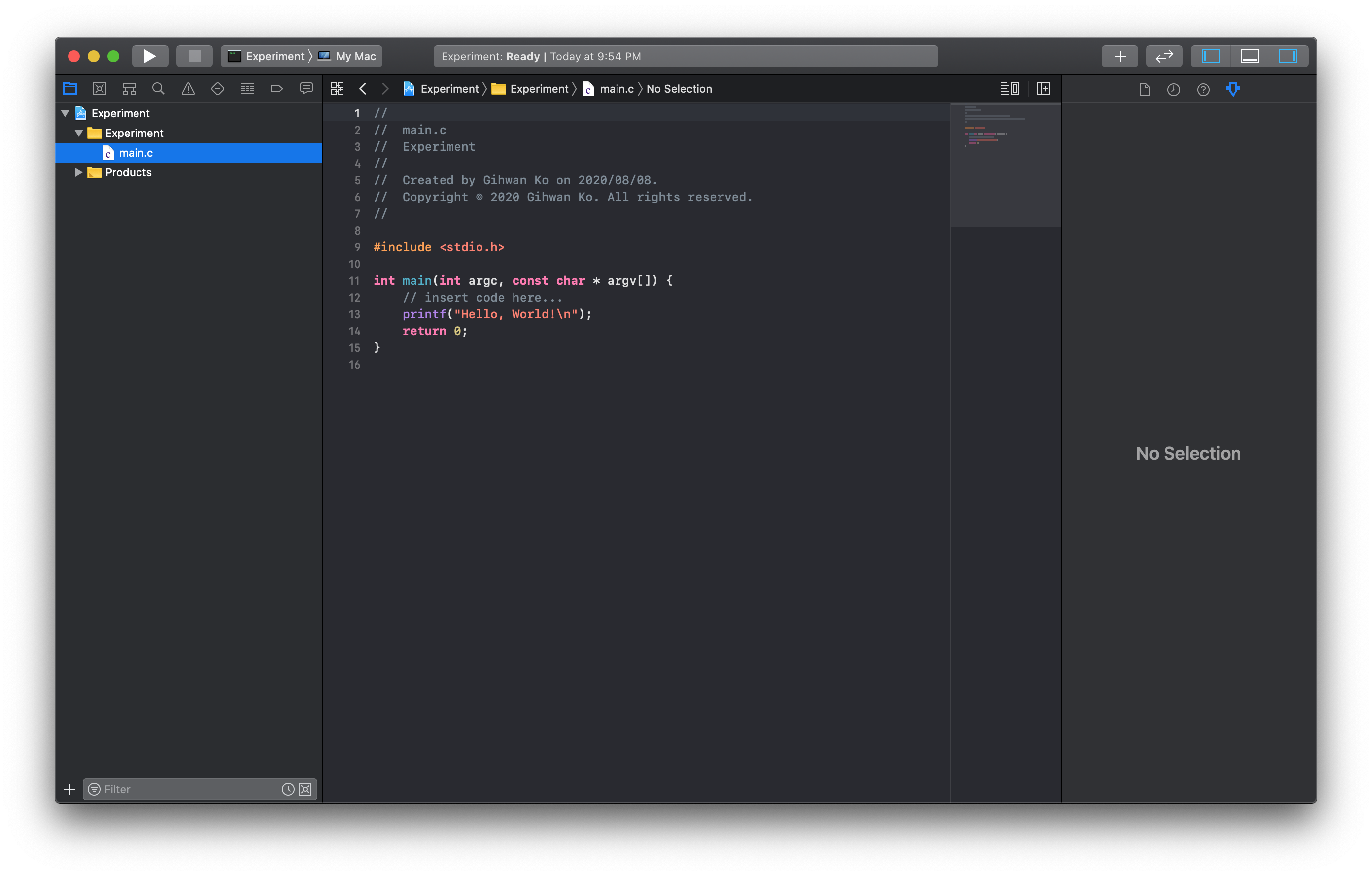

- The left panel shows there is the

main.csource file under theExperimentfolder with minimum codes required to run the program.

Xcode can run a C language program in two different ways: debugging mode and without debugging mode. Hotkey for both are ⌘+R and whether to debug or not is configured on project setting. Debugging mode is used to inspect the problem and visualize the process, otherwise run without debugging is recommended.

Terminal

Linux OS has GCC (GNU Compiler Collection) compiler installed by default but without an IDE. However, IDE is not essential when compiling a source code, which is possible on a terminal as well. With the increasing number of projects starting to use a single-board computer (SBC) like Raspberry Pi, knowing how to develop software in Linux OS became crucial.

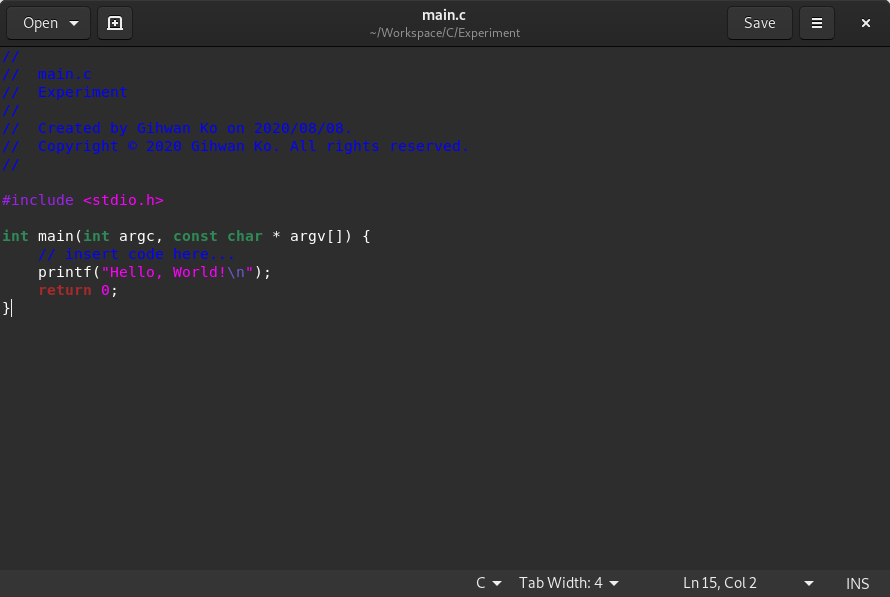

This section uses the code from Figure 11. Creating a C project on Xcode (step 4) to the main.c source file to show how to compile on Linux OS.

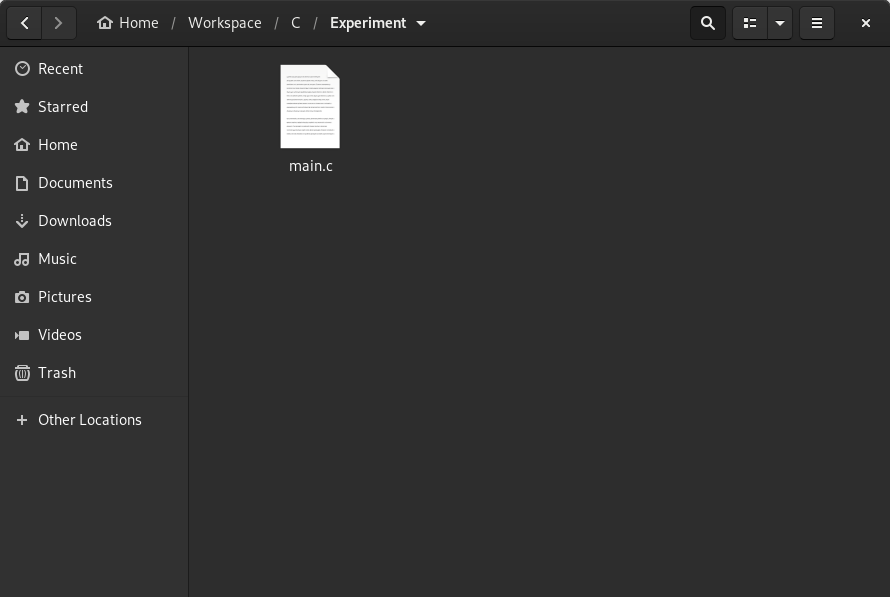

Suppose the main.c source file is at ~/Workspace/C/Experiment directory.

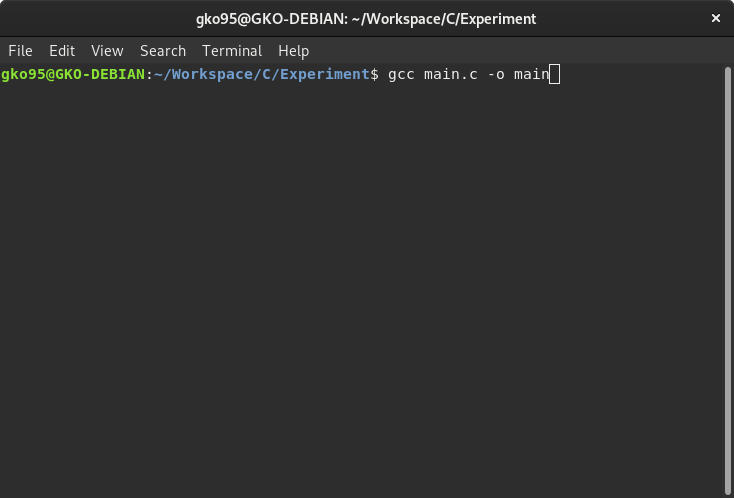

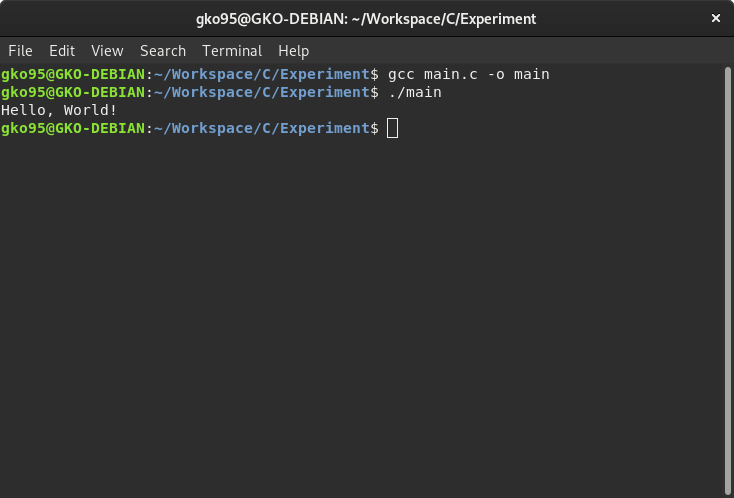

Run a terminal and move to the directory where the source file is; change the current directory with the cd command. Enter the following command to compile the source code with GCC compiler.

The command is ordering to compile the main.c source file and outputs (-o) the main object file. It is one of the simple commands of GCC compiler, and linking external libraries is also possible by adding more options.

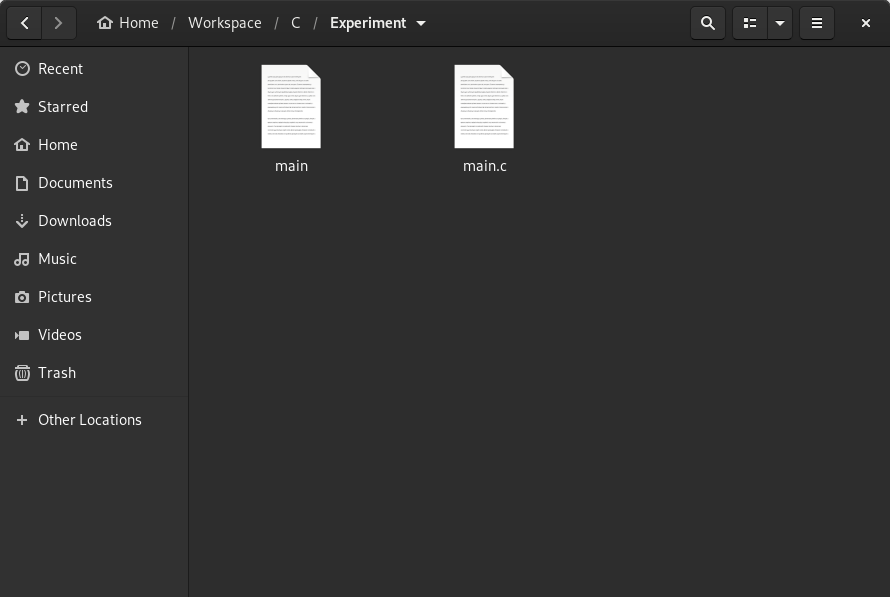

The directory now has an object file called main, compiled from the source code.

To execute an object file from a terminal, place ./ followed by the file name.

Here, the command ./ represents the current directory. Without this command, a terminal wouldn’t be able to find the main file unless the directory is specified by the environment variable.

BASIC

Every programming language has its own rules to be observed and fundamental data that works as a basis of the program. Failed to observe this causes either error or unexpected results. As for the beginning of the practical coding, this chapter will introduce basic knowledge of C language coding.

Header File

A header file is a .h extension file responsible for letting the script know the existence of data or functionalities. Commonly paired with a .c source file, header files can let the other source files to use the data and functionalities defined by its pair.

C language has header files for the source codes already compiled for developers to use, aka. a library. These libraries that come along with a compiler is called the standard library. Following are the header files for some of the C standard library:

| HEADER FILES | SYNTAX | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

stdio |

#include <stdio.h> |

Defines standard input/output function:printf(), scanf() |

stdlib |

#include <stdlib.h> |

Defines various features, such as memory allocation, exception management (cstdlib in C++):rand(), malloc() |

math |

#include <math.h> |

Defines common mathematical functions (cmath in C++):exp(), cos() |

time |

#include <time.h> |

Defines date and time-handling functions (ctime in C++):time(), clock() |

There are two different ways of including a header file to the source code: angled brackets <> and double quotations "".

#include <stdio.h>

#include "header.h"

The difference between these twos is where the preprocessor should search for the header file from:

-

#include <header.h>- search directories pre-designated by the system, compiler, or IDE; this syntax is used to include a system header.

-

#include "header.h"- search from the current local directories where the source file is located. If failed to find the header, automatically search from pre-designated directories, just like

#include <header.h>does; this syntax is used to include a user-defined header.

Precompiled Header

A precompiled header is a header file that compiles into an intermediate form that is faster to process for a compiler. Because it reduces compilation time, a precompiled header is used on the project that includes many header files or a header file with enormous data.

However, using a precompiled header is not always beneficial because it takes more time to prepare for compilation. For a header file that is small or subject to change frequently, a precompiled header is unnecessary.

| PRECOMPILED HEADER | COMPILER |

|---|---|

stdafx.h |

Visual Studio 2015 (msvc14) and below |

pch.h |

Visual Studio 2017 (msvc15) and above |

Statement Terminator

The “statement” in programming represents a code that executes or processes data. In C language, every statement needs to end with a statement terminator denoted by a semicolon ;.

One of the common mistakes made by C language beginners is the absence of a statement terminator. Therefore, developers need to keep this in mind when programming with languages based on C (such as C++ and C#).

Comment

Comment in a programming language is not executed and is commonly used to write down information related to the programming on source codes. There exist two comments in C language: line comment and block comment.

-

- Line comment

- a comment worth a single line of code, declared by

//.

-

- Block comment

- a comment with multiple lines of code, declared by

/* */.

/*

BLOCK COMMENT:

multiple line of comment can be placed here.

*/

// LINE COMMENT: for a single line of code.

Input & Output

C language has several input and output functions for a text-based terminal. Below is a list of output functions:

| OUTPUT | SYNTAX | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

putchar() |

putchar('A'); |

Prints a single character on a console. |

puts() |

puts("Text"); |

Prints sequence of characters (aka. string) on a console; auto new-line. |

printf() |

printf("format", var); |

Prints sequence of characters (aka. string) on a console with formatting. |

fprintf() |

fprintf(stream, "format", var); |

Extension of the printf() function, available with a stream selection; the printf(...) is equivalent to the fprintf(stdout, ...), where stdout is the standard output stream. |

// "putchar()" OUTPUT FUNCTION

putchar('A');

// "puts()" OUTPUT FUNCTION

puts("Hello World!");

// "printf()" OUTPUT FUNCTION

float variable = 3.14159;

printf("variable: %.2f", variable);

AHello World!

variable: 3.14

Below is a list of input functions in C language:

| INPUT | RETURN | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

getchar() |

Character | Reads foremost character as an input. |

gets() |

String (aka. character array) | Reads sequence of characters (aka. string) as an input. |

scanf() |

Format-specific | Reads data as an input in the specified format; requires address (&) operator except for a string. |

// "getchar()" INPUT FUNCTION

char variable1;

variable1 = getchar();

// "gets()" INPUT FUNCTION

char variable2[20];

gets(variable2);

// "scanf()" INPUT FUNCTION

float variable3; char variable4[10];

scanf("%f %3s", &variable3, variable4);

A

>>> variable1 = 'A'

Hello World!

>>> variable2 = "Hello World!"

3.0 Program

>>> variable3 = 3.000000

>>> variable4 = "Pro"

Formatted Specifier

The format specifier is to specify the format on how an input of output function should read or print data. The format specifier works differently depending on input and output.

-

Format specifier on an input function affects the value of data. Slicing characters from a word is one of the examples.

-

Format specifier on an output function maintains the value of data but only affects how it is shown on a terminal. Rounding a decimal point is one of the examples.

int variable;

printf("Enter: ");

scanf("%5d", &variable);

printf("%3d", variable);

Enter: 1234567

12345 // NOT "123" AS SPECIFIED USING "%3d"

| FORMAT | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

%d |

Decimal |

%f |

Floating point number |

%c |

Character |

%s |

String |

%x |

Hexadecimal |

%p |

Pointer |

The

%3dformat specifier does not extract only three front numbers but rather shows three digits at minimum. Hence, the%7dformat specifier would have shown the number0012345.

Identifier

An identifier is a name used to identify data in programming. In other words, it is just a user-defined name. C language has the following rules when naming an identifier:

- Only alphabet, number, and underscore

_is allowed. - First letter cannot start with a number.

- Blank space is prohibited.

Data Type

A data type is one of the crucial factors which determines the type and byte size of the data. A well-implemented data type can make a program efficient on both memory and processing time. C language has several numbers of built-in data type as follows:

| IDENTIFIER | DATA TYPE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

int |

Integer | 32-bits precision integer number. Size: 4 bytes |

float |

Floating point number | Real number with a decimal point. Size: 4 bytes |

double |

Double-precision float | Float with a doubled precision and memory. Size: 8 bytes |

char |

Character: '' |

A single character, such as 'A' or '?'.Size: 1 byte |

void |

Void | Non-specific data type. Size: 1 byte |

NOTICE: ANSI C, the standard compiler for this document, does not support

boolBoolean data type!

sizeof() Function

The sizeof() function returns allocated memory size of the type or data in bytes.

sizeof(int); // SIZE: 4 BYTE

sizeof(char); // SIZE: 1 BYTE

Variable

Variable is a container for data that can be assigned using the assignment operator =. C language must designate a variable with one of the data types, which can only have data with that data type.

The example code below tells a compiler the existence of the variable integer variable. The variable has also allocated memory at the same time to store a value, called definition in programming.

/* DEFINITION OF THE "variable" VARIABLE */

int variable = 3;

A variable may not have any variable but let a compiler know its existence, called declaration in programming.

/* DECLARATION OF THE "variable" VARIABLE */

int variable;

According to the ISO standard for C++, the definition and declaration are the same in general. The detailed documentation is on § 3.1.2 as follows:

A declaration is a definition unless it declares a function without specifying the function’s body (8.4), it contains the extern specifier (7.1.1) or a linkage-specification25 (7.5) and neither an initializer nor a function- body, it declares a static data member in a class definition (9.2, 9.4), it is a class name declaration (9.1), it is an opaque-enum-declaration (7.2), it is a template-parameter (14.1), it is a parameter-declaration (8.3.5) in a function declarator that is not the declarator of a function-definition, or it is a typedef declaration (7.1.3), an alias-declaration (7.1.3), a using-declaration (7.3.3), a static_assert-declaration (Clause 7), an attribute- declaration (Clause 7), an empty-declaration (Clause 7), a using-directive (7.3.4), an explicit instantiation declaration (14.7.2), or an explicit specialization (14.7.3) whose declaration is not a definition.

Although the above documentation is about C++ language, this also applies to C language. Below is a list of cases when a declaration is not a definition.

- Forward declaration of a function

- Declaration of a function’s parameter

externdeclarationtypedefdeclaration

Printing the declared variable above will still show a value, indicating it stores the data despite not having assigned yet. A defined variable does not need to specify the data type as a compiler already knows what type of data it stores. Programming languages, in general, locates assigned data (ex. variable) on the left and assignee (ex. a constant value or another variable) on the right. Otherwise will cause an error or function improperly.

Initialization

Initialization is the first assignment to a variable where it commonly occurs in the definition process.

/* VARIABLE INITIALIZATION */

int variable = 3;

Many believe a definition is equivalent to “declaration + initialization” due to the example code above, but this is a huge misunderstanding. As previously mentioned, a declaration is also considered as a definition in general. The code below is also a definition but without initializing any value.

/* VARIABLE DEFINITION; BUT WITHOUT INITIALIZATION */

int variable;

Local & Global Variable

There are three types of variable in C language:

-

Local variable is a variable defined within the code block, such as functions. A local variable releases data when escapes from the code block and unavailable to use outside. It may have the same name as other variables defined outside the code block.

int main() { // Insert code here... /* LOCAL VARIABLE */ int variable; return 0; } -

Global variable is a variable that does not belong to any code blocks within the script. A global variable can be used with local variables inside other code blocks without any special syntax. Be cautious when using a global variable as it can cause an error related to variable confliction.

/* GLOBAL VARIABLE */ int variable; int main() { // Insert code here... return 0; } -

Static variable is a variation of a local variable that retains the data even after escaping from the code block. The data last left off is continued when re-entering the code block. The

statickeyword declares a static variable.int main() { // Insert code here... /* STATIC VARIABLE */ static int variable; return 0; }

Constant Variable

A constant variable is a variable that cannot change its value after initialization. The const keyword declares variable as a constant.

/* CONSTANT DEFINITION */

const int variable = 1;

Data Type Casting

Data type casting force-changes data type stored in a variable into other desired type. Casting the small size data to a compatible but larger size data type is called implicit casting. Implicit casting is a natural data type conversion automatically done by a compiler as no data loss occurs.

short A = 1; // 2 BYTES INTEGER

int B = A; // 4 BYTES INTEGER

On the other hand, explicit casting risks data loss/corruption upon converting data type. C-style casting syntax uses parenthesis () as follows:

float A = 1.9; // 4 BYTES FLOAT

int B = (int)A; // 4 BYTES INTEGER - INCOMPATIBLE: only returns its integer value.

1

Operator

An operator is the simplest form of the data processing unit that manipulates the value of operands. It is placed before, after, or between the operands.

Arithmetic Operator

The arithmetic operator mainly focuses on processing numeric data types. Following is a list of arithmetic operators used by numeric data type:

| NAME | OPERATOR | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | + |

- |

| Subtraction | - |

- |

| Multiplication | * |

- |

| Division | / |

When both operands are integer: an integer dividend without a remainder. When at least one operand is real (float or double): a real dividend (float or double). |

| Remainder (Modulus Division) | % |

Remainder only returns an integer. |

For easier readability, you may place blank spaces between numbers and operators which does not affect its output.

Assignment Operator

The assignment operator is another operation used within numeric data types. Following is a list of assignment operators used by numeric data type:

| OPERATOR | EXAMPLE | EQUIVALENT |

|---|---|---|

+= |

x += 1 |

x = x + 1 |

-= |

x -= 1 |

x = x - 1 |

*= |

x *= 1 |

x = x * 1 |

/= |

x /= 1 |

x = x / 1 |

%= |

x %= 1 |

x = x % 1 |

Although not an assignment operator, the similar increment and decrement operator has identical meaning as follows:

| OPERATOR | EXAMPLE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

++ prefix |

x = y++ |

x = y; y = y+1; |

++ suffix |

x = ++y |

y = y+1; x = y; |

-- prefix |

x = y-- |

x = y; y = y-1; |

-- suffix |

x = --y |

y = y-1; x = y; |

Relational Operator

The relational operator is used to compare the relation of two values, returning either true or false boolean value. Following is a list of relational operators:

| OPERATOR | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

< |

Lesser than |

<= |

Lesser than or equal to |

> |

Greater than |

>= |

Greater than or equal to |

== |

Equal to |

!= |

Not equal to |

Logical Operator

The logical operator consist of AND, OR, and NOT logic. Consider true and false as binary counterpart of 1 and 0.

| OPERATOR | LOGIC | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

&& |

AND | true when all arguments are true, else false. |

|| |

OR | true when at least one argument is true, else false. |

! |

NOT | Changes true to false and vice versa. |

Escape Character

Escape character \ is used to escape from a sequence of characters and execute certain operations within text-based data. In the introduction on string data type, \n is used to change to a new line.

printf("Hello\nWorld!!");

Hello

World!

| New line | Horizontal tab | Backslash | Backspace | Single quote | Double quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

\n |

\t |

\\ |

\b |

\' |

\" |

CONDITIONAL AND LOOP

Conditional and iteration (or loop) statements are two of the most commonly used in programming. The “statement” in programming represents a code that executes or processes data. This chapter introduces a list of conditional and iteration statements in C language programming.

if Statement

Conditional if statement runs code if the condition holds. When the condition evaluates true, the indented codes are carried out but otherwise ignored.

if (condition)

{

statements;

}

// SIMPLIFIED STATEMENT

if (condition) statement;

The if statement can locate inside another if statement, called “nested if”. Use a code block {} to distinguish between if statements to avoid possible misinterpretation made by a compiler.

if (condition)

{

if (condtion)

{

statements;

}

}

else Statement

A conditional else statement cannot be used alone and must be followed by an if condition. The statement contains code that executes when evaluated false.

if (condition)

{

statements;

}

else

{

statements;

}

else if Statement

A conditional else if statement is a combination of else and if conditions; when the first condition evaluates false, the else if statement provides a new condition different from the previous one.

if (condition) {

statements;

}

else if (condition) {

statements;

}

else {

statements;

}

However, this statement is different from the chain of else-if conditional statement as that is a combination of two sets of conditions. On the other hand, else if conditional statement is a continuation of an existing evaluation instead of starting new conditioning.

Ternary Operator

A conditional statement can be simplified using the ternary operator shown below:

condition ? return_true : return_false;

The vocabulary ternary indicates the statement takes three arguments. The ternary operator should not be overused as it reduces readability but useful on variable assignment.

switch Statement

Conditional switch statement evaluates whether a variable matches a value assigned to the case keyword and executes the corresponding code if true. After execution, the break statement must locate to prevent further evaluation of the next case keyword.

If no condition matches, the statement automatically executes codes under the default keyword that is mandatory. The default keyword does not require the break statement as opposed to the case keyword.

switch (argument)

{

case value1:

statements;

break;

case value2:

statements;

break;

default:

statements;

}

Multiple case keywords may share the same code as follows:

switch (argument)

{

case value1:

default:

statements;

break;

case value2:

case value3:

statements;

break;

case value4:

statements;

break;

}

break Statement

The break statement is to end a loop prematurely. When encountered in the loop, the break statement escapes from the current loop but does not escape from the nesting loop.

continue Statement

The continue statement skips the rest of the code below in the loop and jumps back to the conditioning part. It maintains the iteration rather than escaping from it like the break statement.

while Loop

A while loop statement repeatedly executes statements inside (aka. iterate) as long as the condition holds. The loop ends once the condition evaluates false.

while (condition)

{

statements;

}

// SIMPLIFIED STATEMENT

while (condition) statement;

do-while Statement

The do-while loop statement is similar to the while loop statement, but the former executes code first then evaluates, and the latter is vice versa.

do

{

statements

} while (condition);

for Loop

The for loop statement repeatedly executes statements inside (aka. iterate) as long as the condition holds. Its local variable changes as specified on each iteration, which commonly uses integer increment.

for (variable; condition; increment) {

statements;

}

// SIMPLIFIED STATEMENT

for (variable; condition; increment) statement;

ARRAY

C language can create an array that stores the collection of data. It provides convenience in managing multiple data at once. An array is closely related to a pointer introduced in a later chapter. This chapter describes an array in C language without referring to the pointer.

Array

An array is a container for data of the same data type in sequence. Declare an array by designating its size of how much data it can store using a bracket [].

/* ARRAY DEFINITION */

int arr[size];

A variable is not allowed when defining the size of an array (except a constant). The size of an array is static, meaning it cannot change after the definition.

Assign values in order within a pair of curly bracket {} to initialize an array:

/* INITIALIZATION 1 */

int arr[size] = {value1, value2, ... };

/* INITIALIZATION 2: SIZE IS SET TO THE NUMBER OF ELEMENTS */

int arr[] = {value1, value2, ... };

Upon initialization, the number of initialized values should not exceed its declared size, though it may be smaller, which fills leftover with 0 or NULL value.

Calling an array itself does not show the whole elements inside; instead, it returns the memory address the array data is assigned to (aka. pointer) and is equivalent to the memory address of its first element.

int arr[3] = {value1, value2, value3};

arr; // >> OUTPUT: 0139F854

&arr[0]; // >> OUTPUT: 0139F854

&arr[1]; // >> OUTPUT: 0139F858 ( = 0139F854 + 4 BYTES from integer data type)

This concept is explained later in the next chapter C: POINTER in detail.

Because of this characteristic, an array cannot assign multiple values at once besides initialization. Access each element using a bracket [] with an index starting from 0.

int arr[3];

// ASSIGNMENT TO INDIVIDUAL ELEMENT

arr[0] = value1;

arr[1] = value2;

arr[2] = value3;

Length of Array

When using the sizeof() on the array, it returns the total number of bytes allocated. Since allocated memory size is relevant to the data type, use the following expression to acquire the number of elements:

int arr[3];

sizeof(arr)/sizeof(int); // >> OUTPUT: 3 ( = LENGTH OF ARRAY)

In other words, the length of an array is found by dividing its allocated bytes by its data type size.

Multi-dimensional Array

A multi-dimensional array stores another array as its element. These arrays used as elements must share the same length and data type. A multi-dimensional array can initialize without defining a size but limited to its first boundary only.

/* INITIALIZATION 1 */

int arr[size1][size2] = { {value11, value12, ... }, {value21, value22, ...}, ... };

/* INITIALIZATION 2 */

int arr[][size2] = { {value11, value12, ... }, {value21, value22, ...}, ... };

String

C language does not officially a data type for a string (a sequence of characters) but can substitute with an array of characters with null terminator \0 at the end.

/* C-STYLE STRING */

char arr[] = "Hello"; // arr[] = {'H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', '\0'};

char* ptr = "World!"; // EXPRESSING STRING WITH A POINTER

Below is a list of functions related to a string in C language:

| FUNCTION | EXAMPLE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

strcat() |

strcat(str1, str2); |

Append str2 string at the end of str1 string variable. |

strcpy() |

strcpy(str1, str2); |

Copy str2 string to str1 string variable. |

strlen() |

strlen(str); |

Return the length of str string, excluding a null terminator. |

FUNCTION

C/C++ language is executed based on a single function called the main() function. Understanding the concept of functions is crucial in C/C++ languages and can increase efficiency by creating custom functions, called functional programming. This chapter will be introducing the guide on how to create and use functions in C language for functional programming.

Function

A function is a reusable independent block of code that can process the data and present newly processed data once it’s called, allowing dynamic program scripting. A function is distinguished by parenthesis after its name; function().

int variable = {0, 3, 5, 9};

printf(sizeof(variable));

// USING "printf()" AND "sizeof()" FUNCTION THAT RETURNS THE LENGTH OF A LIST OBJECT.

The function requires two components for a definition:

- Code block

{}: a space for codes that execute when called. - Data type: a type of data to return when exiting the function.

/* FUNCTION DEFINITION */

int function()

{

return 1 + 2;

}

/* CALING A FUNCTION */

function(); // >> OUTPUT: 3

Because C/C++ programming executes from top to bottom sequentially, a function won’t be executable unless it is defined firsthand. However, locating every function definition on top of the script will make it difficult to manage for a larger project.

A function prototype, aka a forward declaration, let the compiler know the existence of a function before the definition. As mentioned in the C: BASIC § Variable section, a forward declaration is not a definition. The prototype is not essential but mostly locates on top of the script, replacing a code block {} to semicolon ;.

/* FUNCTION PROTOTYPE (AKA. FORWARD DECLARATION) */

int function();

/* CALLING A FUNCTION */

function(); // >> 출력: 3

/* FUNCTION DEFINITION */

int function()

{

return 1 + 2;

}

Defining a function inside another function (aka nested function) is invalid in C/C++ language.

return Statement

The return statement is a function-exclusive statement that returns the value processed by a function. Once encountering a return statement, the function ends immediately despite having remaining codes.

If the function is a void data type, the return; statement alone without any data will exit the function.

Parameter & Argument

Following is a difference between parameter and argument mentioned when discussing function:

-

- Argument

- An argument is a value or object passed to a function parameter.

-

- Parameter

- A parameter is a local variable assigned with an argument. Meaning, parameters are only available inside the function. Parameters is declared inside a parenthesis

().

Although parameters and arguments are a different existence, two terms are used interchangeably as both stores the same data.

NOTICE: ANSI C, the standard compiler for this document, does not support

arg=valuedefault argument value!

Examples below show how parameter and argument work in function:

/* FUNCTION PROTOTYPE */

int function(int arg1, float arg2);

/* CALLING A FUNCTION */

function(1, 3.0); // >> OUTPUT: 4.0 (extract an integer from 1 + 3.14)

/* FUNCTION DEFINITION */

int function(int arg1, float arg2)

{

return arg1 + arg2;

}

Passing a container such as an array cannot be done using the syntax above and requires a different method. There are two syntaxes available: defining a parameter as an array or as a memory address (pointer).

void function(int arg[]);

int arr[3] = {value1, value2, value3};

function(arr); // PASSING ARRAY TO FUNCTION ARGUMENT

// ACCEPT ARGUMENT AS AN ARRAY

void function(int arg[])

{

statements;

return;

}

void function(int *arg);

int arr[3] = {value1, value2, value3};

function(arr); // PASSING ARRAY TO FUNCTION ARGUMENT

// ACCEPT ARGUMENT AS A POINTER

void function(int *arg) {

statements;

return;

}

The latter method is possible due to the characteristic where calling an array itself returns the memory address of the first element. Incrementing the pointer will shift to the next element since the memory is allocated in sequence.

Entry Point

An entry point is the startup function where program execution begins; C language is the main() function and does not need forward declaration nor needs to be called. There can be only one entry point in the project; having more than one entry point or none will result in an error.

/* C LANGUAGE ENTRY POINT: main() */

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

// Insert code here...

return 0;

}

As the only entry point available in traditional C console application, a project must have one and only main() function within the project. Creating multiple main() functions or not having any main() function will cause error on running the program.

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

return 0;

}

While this article didn’t include the main() function on the example codes, every code besides global variables and function definitions must be inside the entry point.

According to the C language standard, the main() function must return an integer; the EXIT_SUCCESS (equivalent to an integer 0) or the EXIT_FAILURE.

The compiler implicitly fills in the return 0; statement at the end of the entry point if not presented in the function.

The main() function has the following parameters:

argc: the number of arguments (abbrev. of argument count)argv: the list of argument values (abbrev. of argument vector); alternatively can be declared aschar *argv[]

These arguments are apparent when running the program on a terminal:

./app.exe option1 option2

| ARGUMENTS | VALUE |

|---|---|

argv[0] |

./app.exe |

argv[1] |

option1 |

argv[2] |

option2 |

The argc parameter always has a value greater than zero since the first element of the argv is the name of the program.

Meanwhile, Windows OS has an exclusive entry point called the wmain() function that supports various languages by using wide-character arguments encoded in UTF-8 Unicode (size varying from 1~4 bytes).

/* C LANGUAGE ENTRY POINT SUPPORTING WIDE-CHARACTER: wmain() */

int wmain(int argc, wchar_t **argv) {

return 0;

}

The wmain() function was introduced because C language originated from UNIX operating system interface based on ASCII encoding. Using the main() function on Windows OS won’t recognize certain characters, such as Greek, Cyrillic, due to encoding compatibility.

Recursion Function

A recursive function is a function that calls itself (recursion). Factorial in mathematic is the best example of recursive function implementation.

/* EXAMPLE: FACTORIAL "!" */

int factorial(int num) {

// BASE CASE: a case when to escape from the recursion.

if (num == 1)

return (1);

else

return (num * factorial(num-1));

}

Recursion can occur indirectly by multiple functions calling one to another, then back to the beginning.

Callback Function

The callback function, aka. “call-after” function, is a function passed as an argument to other functions. The calling function runs the callback function by calling the parameter, thus named as the “callback” function.

The following is the example for the callback function, which is explained in the C: POINTER § Function Pointer section.

/* CALLING FUNCTION */

int calling(float (*function)(int, float), int arg)

{

// CALLING CALLBACK FUNCTION

float var = function(arg, 3.0);

return var;

}

/* CALLBACK FUNCTION */

float function(int arg1, float arg2) {

return arg1 + arg2;

}

// THEREFORE...

FUNC(&function, 1, 3.0); // >> OUTPUT: 4.0

POINTER

This article has mentioned a new “pointer” data type since the C: ARRAY chapter. The pointer is one of the crucial concepts in C language, allowing more complex programming. This chapter describes what the pointer is in C language and revisits the array and function.

Pointer

The pointer is a data type that stores the allocated memory address of a variable instead of its value. A 32-bit and 64-bit operating system have a pointer that is 8 and 16 bytes long. A variable can store a pointer as well; while the data type is required when defining, an asterisk * must locate between the data type and identifier.

/* POINTER DECLARATION */

int* ptr;

printf("%p", ptr); // WARNING C4700: UNINTIALIZED LOCAL VARIABLE 'ptr' USED

Memory address can be called from a non-pointer variable as well using the ampersand operator &.

/* INTEGER VARIABLE DEFINITION */

int variable = 365;

printf("%p", &variable);

1014eb010

Since the hexadecimal memory address should not be written by hand, the only way to assign the pointer is by the existing memory address. Beware, the data type must match on assignment to the variable.

While a memory address is expressed in eight bytes (32-bit architecture) or sixteen bytes (64-bit architecture) of hexadecimal, a single memory is limited to hold data of one byte. The char data type is enough with a single byte, but the int integer or float floating-point number requires four bytes of memory space. However, since the pointer only returns the first memory address of overall memory space, the compiler won’t know whether the data is complete when the data type is not specified.

/* VARIABLE INITIALIZATION */

int variable = 365;

// POINTER VARIABLE OF THE SAME TYPE

int *ptr1 = &variable;

printf("%p\n", ptr1); // >> OUTPUT: 0x1014eb010 (ADDRESS)

printf("%d\n", *ptr1); // >> OUTPUT: 365 (VALUE)

// POINTER VARIABLE OF THE DIFFERENT TYPE

char *ptr2 = &variable;

printf("%p\n", ptr2); // >> OUTPUT: 0x1014eb010 (ADDRESS)

printf("%d\n", *ptr2); // >> OUTPUT: 109 (VALUE)

As seen above, it is possible to return the value assigned to the pointer by placing the dereference operator *. While a pointer declaration also used an asterisk, they are different existence but only sharing the same symbol.

| OPERATOR | VARIABLE | RETURN |

|---|---|---|

Address-on Operator & |

Non-pointer | Memory address |

Contents-of Operator * |

Pointer | Value |

If the variable value changes, the value dereferenced from the pointer also changes since it shares the same memory address, also known as “call by reference”.

Null Pointer

A null pointer is a pointer that points to nothing. Since C language may cause an error such as memory access violation because of the pointer, assign the NULL keyword for safe usage.

int* ptr = NULL;

printf("%p", ptr);

0x0

Void Pointer

A void pointer is a pointer with no specific data type (thus, void). It has the advantage of being able to point to any data type with help from data type conversion.

/* VOID POINTER DECLARATION */

void *ptr;

int variable = 356;

ptr = &variable;

printf("%d", *(int*)ptr);

365

Function Pointer

The function pointer is a void pointer that points to a function. Similar to a pointer to an array representing the first element memory address, a function pointer points to the first line of the function code. Initialize the function pointer using the following syntax:

/* FUNCTION DEFINITION */

int function(int arg1, float arg2) {

statements;

return 0;

}

int main() {

// Insert codes here...

/* FUNCTION POINTER INITIALIZATION */

int (*ptr)(int, float) = function;

ptr(1, 3.14);

return 0;

}

The function pointer should match the data type and parameters of the function when initializing. Failed to do so will result in a compilation error. While calling with a parenthesis like function() returns data from the return statement, without a parenthesis like function returns a memory address instead.

USER-DEFINED DATA TYPE

Commonly used data types such as int, float, char, and more are already defined and are called through the stdio.h header file. This chapter introduces defining a new user-defined data type that is similar to these data types but can store multiple data in a single variable.

Structure

The structure is a user-defined data type that integrates multiple variables as members of a single structure tag regardless of their data type. Use the struct keyword to define a structure.

/* STRUCTURE DEFINITION: TOTAL 5 BYTES */

struct STRUCTURE {

// MEMBER VARIABLE DEFINITION

int field1; // TYPE SIZE: 4-BYTE

char field2; // TYPE SIZE: 1-BYTE

};

There are two methods for defining a variable from the structure, and both require the struct keyword.

/* STRUCTURE VARIABLE INITIALIZATION 1 */

struct STRUCTURE variable1 = {3, 'A'};

struct STRUCTURE variable2 = {.field2 = 'A', .field1 = 3};

/* STRUCTURE VARIABLE DEFINITION */

struct STRUCTURE variable;

/* STRUCTURE VARIABLE INITIALIZATION 2 */

variable = (struct STRUCTURE) {3, 'A'};

After defining a structure variable, the struct keyword is not needed, and its members are accessible by the member access operator ..

variable.field1; // >> OUTPUT: 3

variable.field2; // >> OUTPUT: A

Anonymous Structure

The syntax for the structure in the previous section is reusable and can create more than one structure variable of the same type. However, to create a user-defined data type for a single-use, define the anonymous structure using the syntax below:

/* SINGLE-USE STRUCTURE VARIABLE DEFINITION & INITIALIZATION */

struct {

int field1;

char field2;

} variable = {3, 'A'};

Union

The union is a user-defined data type that integrates multiple variables as members of a single structure tag regardless of their data type but shares a memory space. In other words, value changes in one of the members also change the value assigned in the other members. Use the union keyword to define a union.

/* UNION DEFINITION: TOTAL 4 BYTES */

union UNION {

// MEMBER VARIABLE DEFINITION

int field1; // TYPE SIZE: 4-BYTE

char field2; // TYPE SIZE: 1-BYTE

}

The byte size of the union is equal to the member variable with the largest byte size; this allows the user-defined data type to use a single memory allocation while still have enough space to store other data types.

Use the following syntax to define a variable from the union, which requires the union keyword. Although the union data type may have more than one member, only one member needs initialization as they all shares the same memory space.

/* UNION VARIABLE INITIALIZATION */

union UNION variable = (union UNION) {365}; // >> OUTPUT: 0x 00 00 01 6D

printf("Field1: %d (%#010x)\n", variable.field1, variable.field1);

printf("Field2: %d (%#010x)\n", variable.field2, variable.field2);

Field1: 365 (0x0000016d)

Field2: 109 (0x0000006d)

The first member, field1, is a 4-byte data type that processes all of 0x0000016D bytes and returns an integer 365. However, the second member, field2, is a 1-byte data type that can only process a single byte, resulting in an integer 109.

Anonymous Union

The syntax for the union in the previous section is reusable and can create more than one union variable of the same type. However, to create a data structure for a single-use, define the anonymous union using the syntax below:

/* DEFINING & INITIALIZING A SINGLE-USE UNION VARIABLE */

union {

int field1;

char field2;

} variable = {365};

Enumeration

The enumeration is a user-defined data type numbering enumerating items, called enumerators. Enumerators are assigned with an integer that starts from zero and increments by one by default.

The original C compiler “K&R C” did not have the enumerator, but is added since the commonly used “ANSI C” compiler.

/* ENUMERATION DEFINITION */

enum ENUMERATION {

enumerator1, // ENUMERATOR = 0

enumerator2, // ENUMERATOR = 1

enumerator3, // ENUMERATOR = 2

enumerator4 // ENUMERATOR = 3

};

Assigning an integer is done using the assignment operator =. The other enumerators may share the same value.

enum ENUMERATION {

enumerator1 = 3, // ENUMERATOR = 3

enumerator2 = 1, // ENUMERATOR = 1

enumerator3, // ENUMERATOR = 2

enumerator4 // ENUMERATOR = 3

};

However, enumerators cannot share the same identifier, which is similar to a global constant. In other words, enumerators are global data used across the project but unchangeable after initialization.

enum ENUMERATION1 {

enumerator1,

enumerator2,

enumerator3,

enumerator4

};

enum ENUMERATION2 {

enumeration4, // ERROR: Enumerator 'enumerator4' is re-defined.

enumeration5,

enumeration6

};

Defining an enumeration variable requires the enum keyword but is not needed when calling the variable afterward. An integer variable can also store an enumerator from the enumeration.

/* ASSIGNING ENUMERATOR TO AN ENUMERATION VARIABLE */

enum ENUMERATION variable = enumerator1;

/* ASSIGNING ENUMERATOR TO AN INTEGER VARIABLE */

int variable = enumerator1;

Typedef Declaration

The typedef keyword aliases the existing data type to a different name, providing better readability.

typedef int dtypeName;

The keyword can also simplify the definition of structures and unions in C language programming.

/* SIMPLIFIED STRUCTURE DEFINITION */

typedef struct {

int field1;

char field2;

} STRUCTURE;

STRUCTURE variable; // struct STRUCTURE variable;

variable = (STRUCTURE) {3, 'A'}; // variable = (struct STRUCTURE) {3, 'A'};

/* SIMPLIFIED UNION DEFINITION */

typedef union {

int field1;

char field2;

} UNION;

UNION variable; // union UNION variable;

variable = (UNION) {365}; // variable = (union UNION) {365};

User-Defined Data Type Pointer

When defining a user-defined data type as a pointer, access the members using the arrow member selection operator ->. In general, this syntax is for accessing the members passed to the function parameter by reference.

/* STRUCTURE DEFINITION */

struct STRUCTURE {

int field1;

char field2;

};

/* VARIABLE & POINTER DEFINITION */

struct STRUCTURE variable;

struct STRUCTURE *ptr = &variable;

ptr->field1 = 3;

ptr->field2 = 'A';

// THEREFORE...

printf("%d\n", ptr->field1);

printf("%c\n", ptr->field2);

3

A

DYNAMIC ALLOCATION

Memory management in C language is a significant task. Dynamic memory allocation provides higher memory efficiency but requires a clear understanding of the pointer as it is deeply involved. Here, the memory indicates random access memory (RAM), the primary memory in a computer.

Stack Structure

The stack is a linear LIFO (Last-In-First-Out) data structure; the first entered data is last to be freed from the memory structure. It is the main memory structure used by the compiler that automatically allocates and deallocates data upon declaration and destruction of data, such as variables and functions. The drawback of stack-based memory is poor memory management.

The characteristic of the stack memory is apparent when dealing with a local variable, which is unable to use outside the code block.

Queue Structure

The queue is a linear FIFO (First-In-First-Out) data structure. The data that entered first is released first from the memory structure. The best example of a queue-based memory structure is serial communication, such as USB and ethernet.

Dynamic Allocation

Despite its fast memory allocation, the stack memory is difficult for memory management due to its sequential structure. Additionally, the purpose of a stack-based memory used by the compiler is not for storing data but rather to “process data,” hence have limited capacity on RAM. However, the compiler can also access the heap memory region located in the same RAM. Although slower than the stack, it has the benefit of easier management and lasting data until the end of the program.

The heap memory region is irrelevant to the heap data structure and is purely a term that indicates part of the RAM.

Allocating memory in the heap region is called dynamic allocation in C language. Developers need to use a specific function for dynamic allocation, where the allocation address is randomly designated. Since this process is done manually by the developers, every dynamically allocated data must be freed by the developers as well. Failed to do so will cause the program to crash from memory shortage or function improperly.

Include the stdlib.h header file for dynamic allocation.

| FUNCTION | EXAMPLE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

malloc() |

malloc(size); |

Allocate size-byte heap memory block; memory uninitialized, resulting SEGFAULT error. |

calloc() |

calloc(num, size); |

Allocate size-byte heap memory blocks num times contiguously; initialized to 0 but slower than malloc(). |

realloc() |

realloc(ptr, size); |

Reallocate to size-byte heap memory block. |

free() |

free(ptr); |

Release dynamically allocated memory. |

#include <stdlib.h>

/* DYNAMIC ALLOCATION: 10 BYTES */

int* ptr = malloc(10);

/* REALLOCATION: 10 -> 20 BYTES */

ptr = realloc(ptr, 20);

/* DYNAMIC DEALLOCATION */

free(ptr);

Dynamic Array

A dynamic array represents an array that has dynamic sizing, unlike the usual array in C language that can only have an unchangeable static size. It requires both structure and dynamic allocation, created as shown below:

#include <stdlib.h>

/* SIMPLIFIED STRUCTURE DEFINITION */

typedef struct {

int* arr; // ARRAY ELEMENTS

int size; // ASSIGNED SIZE

int capacity; // ARRAY LENGTH

} dynamicArr;

/* DYNAMIC INTEGER ARRAY DEFINITION */

dynamicArr variable;

/* DYNAMIC ARRAY: 4 BYTE LENGTH */

variable.arr = calloc(1, sizeof(*variable.arr));

variable.capacity = 1;

/* DYNAMIC ARRAY: REALLOCATE ADDITION 20 BYTES */

variable.arr = realloc(variable.arr, (variable.capacity + 5) * sizeof(*variable.arr));

variable.capacity += 5;

Memory Leak

A memory leak is caused by mismanagement of heap memory when dynamically allocated data is not released (deallocated) and accumulated that no more heap memory space is available. A shortage of memory will eventually lead to system failure. Prevent memory leak by deallocating data on heap memory using the free() function.

/* DYNAMIC DEALLOCATION */

free(ptr);

Dangling Pointer

By deallocating data on heap memory prevents memory leak from happening. While the data addressed by the pointer is gone, it still holds the address that now points to the unknown, called dangling pointer that may cause the SEGFAULT, a segmentation fault error. Assign the NULL so the pointer would point at least to nothing rather than point aimlessly after deleting the heap memory data.

/* PROPER DEALLOCATION: DELETE DATA ON POINTED MEMORY -> NULLIFY POINTER */

free(ptr);

ptr = NULL;

FILE MANAGEMENT

C language can read and write external files to save or load data. This chapter focuses on accessing and modifying the .txt extension text file.

Opening Files

The file first needs to be opened to either read or write. Opening the file is done using the fopen() function that returns a pointer to the FILE data type. The mode argument must be selected to specify whether the file is for reading or writing.

/* OPENING FILE */

FILE* fptr = fopen("sample.txt", mode);

| MODE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

"r" |

Open for reading (the file must exist) |

"w" |

Open for writing (creates the file if not exist) |

"a" |

Open for appending (creates the file if not exist) |

"r+" |

Open for reading and writing from beginning |

"w+" |

Open for reading and writing, overwriting the file |

"a+" |

Open for reading and writing, appending to the file |

Reading Files

C languages has three different functions for reading similar to input (from file to program) functions:

| INPUT | SYNTAX | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

fgetc() |

fgetc(fptr); |

Reads the next character from the selected fptr file stream. |

fgets() |

fgets(buff,n,fptr) |

Stores n-1 long characters from the fptr file stream to a buffer (ex. char buff[100];) with a null terminator \0 at the end. |

fscanf() |

fscanf(fptr,"format",vars) |

Stores data, separated by spaces or new lines, to variables vars according to the format specifier from the fptr file stream; requires address operator & except for the string. |

<sample.txt>

Hello World!

65 3.14159

/* READING "sample.txt" FILE */

FILE* fptr = fopen("sample.txt", "r");

// "fgetc()" FUNCTION

char variable1;

var1 = fgets(fptr);

// >> RESULT: variable1 = 'H'

// "fgets()" FUNCTION

char buff[10];

fgets(buff, 7, fptr);

// >> RESULT: buff = "ello W"

// "fscanf()" FUNCTION

char[10] variable2; int variable3; float variable4;

fscanf(fptr, "%s %d %f", var2, &var3, &var4);

// >> RESULT: variable2 = "orld!", variable3 = 65, variable4 = 3.141590

Writing Files

C languages has three different functions for writing similar to output (from program to file) functions:

| OUTPUT | SYNTAX | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

fputc() |

fputc(char,fptr); |

Writes a single character to the fptr file stream. |

fputs() |

fputs(str,fptr); |

Writes sequence of characters (aka. string) to the fptr file stream. |

fprintf() |

fprintf("%d",var); |

Writes sequence of characters (aka. string) to the fptr file stream with a format support. |

/* WRITING FILE */

FILE* fptr = fopen("sample.txt", "w");

// "fputc()" FUNCTION

fgets('A', fptr);

// "fputs()" FUNCTION

fgets("Hello World!\n", fptr);

// "fprintf()" FUNCTION

fprintf(fptr, "%d %.2f %s", 1, 3.14159, "Program");

<sample.txt>

AHello World!

1 3.14 Program

Creating Files

A new file can be created using the same method of writing a file that does not bound by just writing on the existing file. Creating a file is done simply by designating a file name that doesn’t exist on the specified path.

/* CREATING FILE */

FILE* fptr = fopen("path\\new_file.txt", "w");

fgets("Hello World!\n", fptr);

Closing Files

After opening the file, it should be closed manually. Opened file is closed using the fclose() function.

/* CLOSING FILE */

fclose(fptr);

The function returns an integer 0 if successfully closed, otherwise returns EOF (end of file).

MULTI-SCRIPT PROJECT

This article has mainly dealt with a project that only consists of a single script with the main() function. If the project starts to grow larger, however, additional scripts can help manage the project more efficiently by dividing and categorizing the codes. This chapter will explain how to create a C language project with multiple scripts sharing the data.

Inclusive Directive

The #include inclusive directive is one of the preprocessor directives, commonly used to include the stdio.h header to a source file. Technically, what the #include does is paste the entire codes such as declaration in the header file to where the directive is.

Header & Source File

The source and header file first mentioned at the beginning of the chapter C: BASIC has its purposes as follows: the former is a script that contains definitions, and the latter contains declarations. Considering that the main() function does not have a prototype, the main script can be written as follows:

/* HEADER FILE: main.h */

#include <stdio.h>

int variable;

void function(int, float);

/* SOURCE FILE: main.c */

#include "main.h"

int main(){

variable = 'A';

printf("%c\n", variable);

function(1, 3.14);

return 0;

}

void function(int arg1, float arg2){

printf("%.3d\n", arg1 + arg2);

}

A

4.140

The source and header file above is equivalent to the script below due to the property of the #include directive.

/* #include "main.h": START */

#include <stdio.h>

int variable;

void function(int, float);

/* #include "main.h": END */

int main(){

variable = 'A';

printf("%c\n", variable);

function(1, 3.14);

return 0;

}

void function(int arg1, float arg2){

printf("%.3d\n", arg1 + arg2);

}

extern Keyword

The extern keyword can only declare without definition. Although the declaration is the same as the definition in general, the extern keyword is one of the cases that is not. Hence, this section requires to know the difference between declaration and definition for sure.

Defining a variable or function allocates memory for that data, thus can only define once per data. Meanwhile, declaring data does not allocate memory but only lets the compiler know its existence, hence can declare multiple time for a single data. Such property is crucial for a script to share its variables and functions with the other.

/* HEADER FILE: module.h */

#include <stdio.h>

// VARIABLE DECLARTION USING "extern" KEYWORD

extern char variable;

void function(int, float);

/* SOURCE FILE: module.c */

#include "module.h"

// VARIABLE DEFINITION

char variable = 'A';

void function(int arg1, float arg2){

printf("%.3f\n", arg1 + arg2);

}

/* MAIN SCRIPT */

#include <stdio.h>

#include "module.h"

int main() {

printf("%c\n", variable);

function(1, 3.14);

return 0;

}

A

4.140

If the module.h header file does not use the extern keyword, the variable is defined instead of being declared. Variable defined on both the header and source file results in compilation error due to re-definition.

On the other hand, the extern keyword allows data declaration multiple times. Variable declared on both the header and source file doesn’t cause any error to the compiler but requires a definition to use the data. The char variable = 'A'; statement in the module.c source file is for that definition, allowing the main script to use the variable globally with the defined value.

EXCEPTION

An exception is an inexecutable code error due to incorrect coding or input. Because it is not an error filtered upon compilation, a successfully built program immediately halts when encountering an exception. C language has functions and macros for handling exceptions: errno, perror(), and strerror(), and more. Exception handling aims to provide a stable program without any halt or crash.

Error Number

The error number, aka. errno macro, is a global variable defined in the errno.h header file. The variable first needs to be initialized to 0 before using, and a new error number is assigned whenever encountering an error. For Windows OS, the description of the error number is available on Windows Developer document.

Following script is one of the examples of the errno usage by attempting to open a non-existing file:

/* "errno.h" HEADER FILE */

#include <errno.h>

/* errno GLOBAL VARIABLE DECLARATION */

extern int errno;

int main(){

/* errno GLOBAL VARIABLE INITIALIZATION */

errno = 0;

FILE* fptr = fopen("./non_existance.txt", "r");

// FAILED TO OPEN THE FILE...

if (fptr == NULL) {

// ERROR NAME & NUMBER: ENOENT 2 (No such file or directory)

fprintf(stderr, "Error opening a file! ERROR CODE: %d\n", errno);

exit(-1);

}

fclose(fptr);

return 0;

}

Error opening a file! ERROR CODE: 2

Standard Error Stream

The C: BASIC § Input & Output section first introduced the most common output stream: the stdout standard output stream. There are other kinds of stream designed for streaming errors, which is stderr standard error stream.

A stream is “a continuous flow of liquid, air, or gas.” In terms of computer communication, a stream means a path of data flow.

fprintf(stderr, "Hello World!");

This distinguishment on streams allows selective control of transmitting data from the program to target devices/locations, such as a terminal or file.

Error Description

The errno macro stores various errors expressed in integer to the global variable. However, to get the description of the error as a text instead, use the perror() function as shown below:

int main(){

FILE* fptr = fopen("./non_existance.txt", "r");

if (fptr == NULL) {

// ERROR NAME & NUMBER: ENOENT 2 (No such file or directory)

perror("ERROR DESCRIPTION");

exit(-1);

}

fclose(fptr);

return 0;

}

ERROR DESCRIPTION: No such file or directory

PREPROCESSOR

C language compiler processes the script into two divided stages: preprocessing and compilation. On the stage of preprocessing, preprocessor directive such as #include is taken care of by the compiler. This chapter will introduce useful and commonly used preprocessor directives that is being implemented on development.

Macro Definition

A macro is a fragment of code that has a name (aka. identifier). These pieces of code can be simple data (such as a number, character, and string) or an expression with arguments. The formal and latter are respectively called the object-like and function-like macro.

A macro has a benefit that cannot change on runtime. A header file is where macros are generally defined, which passes to the source file via the #include inclusive directive.

#define Directive

The #define directive creates a new macro.

#define SOMETHING value // OBJECT-LIKE MACRO

#define ANYTHING(x, y) (x * SOMETHING - y) // FUNCTION-LIKE MACRO

#undef Directive

The #undef directive removes a defined macro. In some cases, this macro can resolve an error caused by naming collision due to other macros.

#undef SOMETHING

Predefined Macros

Compilers have common standard and compiler-specific predefined macros available for developers. Below is a list of links to the document on predefined macros such as MSVC, GCC, and more.

- MSVC: Microsoft Docs - Predefined Macros

- GCC: GCC Online Documentation - Predefined Macros

- Others: SourceForge Wiki

Conditional Inclusion

A conditional inclusion is a directive for conditional compilation; the compiler ignores the codes when the condition is false.

#if SOMETHING > value

statements;

#elif SOMETHING < value

statements;

#else

statements;

#endif

These directives are not for the substitution of if and else conditional statement despite having similar traits on evaluating the condition.

Macro Condition

A conditional inclusion can also evaluate whether the macro is defined or not.

// IF COMPILED ON 64-BIT ARM OR x64 ARCHITECTURE...

#ifdef _WIN64

statments;

#endif

// IF NOT COMPILED ON 64-BIT ARM OR x64 ARCHITECTURE...

#ifndef _WIN64

statements;

#endif

Pragma Directive

A pragma directive is for configuring features and options for a compiler. Compiler developed by different companies or organizations differs from each other, and this makes pragma a non-standard compiler-specific preprocessor directive.

The Pragma is an abbreviation of the word “pragmatic: a practical consideration.” The directive may have been named with such a term as it involves how the compiler practically works and processes.

- MSVC: Microsoft Docs - Pragma Directives and the Pragma Keyword

- GCC: GCC Online Documentation - Pragmas

This chapter focuses on pragma directives from MSVC as it is the most common and widely used C compiler provided by Microsoft Visual Studio.

#pragma once

The #pragma once pragma directive only includes the header file once instead of multiple times on every inclusion.

#pragma once

Because it prevents including the same header file multiple times for a single source file that can cause a re-definition problem, #pragma once is commonly used for include guard. Additionally, this pragma directive can reduce compilation time as it only includes the header once.

The following code is an example of include guard without using the #pragma once directive:

/* HEADER FILE: "header.h" */

#ifndef HEADER_FILE

#define HEADER_FILE

#endif /* HEADER_FILE */

If the header.h has not been processed, the compiler defines the HEADER_FILE for the first time. However, on the second encounter, the compiler will not process the header file again because of the macro conditioning.

#pragma region

Although it does not affect any on the compilation, the #pragma region and #pragma endregion pair supports expanding and collapsing code block on Visual Studio code editor.

#pragma region REGIONNAME

statements;

#pragma endregion